ECONOMIC COMMENTARY: MAX GILLMAN

Max Gillman, author of The Spectre of Price Inflation (2023), holds the title of Friedrich A. Hayek Professor of Economic History at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. His interest in the value of money began with his 1987 Ph.D. dissertation, The Time Value of Money, completed at the University of Chicago. His dissertation committee included Nobel laureates Robert E. Lucas, Jr. (chair) and Gary S. Becker, as well as renowned econometrician Yair Mundlak. This early academic foundation influenced his lifelong dedication to the study of monetary economics and inflation.

The Spectre of Price Inflation

This book makes a significant contribution to the longstanding debate between monetarist and Keynesian views of inflation’s causes. The first, the monetarist tradition, traces its roots to Irving Fisher’s The Purchasing Power of Money (1911), which formalized the Quantity Theory of Money, and later to Milton Friedman’s A Program for Monetary Stability (1960). This school posits that inflation is fundamentally a monetary phenomenon: when the money supply expands faster than real output, prices rise proportionally—a relationship distilled in Friedman’s famous axiom that inflation is “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon“.

In stark contrast, the Keynesian view, articulated in John Maynard Keynes’ A Treatise on Money (1930) and The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), rejects this direct causality. Instead, it attributes inflation to asymmetric price adjustments and market power. Keynesians argue that inflation emerges when firms with pricing power (e.g., monopolies or oligopolies) initiate mark-up increases, followed by slower, staggered adjustments across the economy due to rigidities. This process results in economy-wide price rises, that is, inflation.

Gillman is a monetarist who blames the Fed for the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) due to negative real interest rates (i.e., the federal funds rate being lower than the CPI from 2002-2004) that actually paid mortgage borrowers to take loans. When real interest rates started to increase, borrowers were unable to service their debts to banks.

However, the Fed helped investment banks – which were uninsured by the FDIC – by bailing them out using excess reserves, as they were deemed “too big to fail“. Instead of bringing investment banks into the FDIC system, post-GFC reforms advocated for increasing reserve levels for individual banks. In mid-March 2020, the reserve requirement ratios were abolished at a time when excess reserves amounted to over $1 trillion (p. 160). Pandemic-related panic and withdrawals led the Fed to again resort to central bank liquidity swaps.

Central bank liquidity swaps are agreements between the Fed and foreign central banks to exchange currencies temporarily. The Fed prints new money and sells US dollars to foreign central banks. In return, the Fed receives an equivalent amount of the foreign central bank’s currency, with an agreement to reverse the transaction at a later date. Value of liquidity swaps rose to around 500 billion dollars in 2008, causing the first buildup of excess reserves, according to Gillman (p. 157). Gillman finds these swaps to be “smoke and mirrors” for printing fresh money and adding it to reserves. Moreover, he explains that M1 calculations historically omitted most demand deposits held by shadow banks, distorting money supply data reliability. In May 2020, the Fed redefined M1 to include money market demand accounts.

To explain build-up of excess reserves, Gillman writes that commercial banks first purchase government bonds in the primary market. Central banks later acquire these bonds from commercial banks in the secondary market. During this period, inflation remains stable because commercial banks hold the proceeds as reserves at central banks rather than lending or investing them. Increased reserves expand the monetary base but don’t directly impact inflation unless banks lend or invest these reserves. Inflation arises only when reserves are used to create loans or investments, as this introduces newly created money into circulation. This also stifles productive investment as banks don’t lend out their reserves but keep them with the Fed.

Gillman criticizes the Fed for fixing the interest on excess reserves (IOER) rate, which has primarily remained below the inflation rate since the GFC, as well as fixing money market rates below inflation after 2001. This has resulted in persistently negative real interest rates: “Not only was the IOER rate a fixed rate set by the Fed, but it also constrained other short-term interest rates near to the same level” (p. 184). The primary losers in this scenario are savers, pension funds and insurance companies, who face diminished returns on their investments. Other countries adopted similar policies to the U.S., as maintaining higher real interest rates would have caused capital inflows, appreciating their currencies and harming export-oriented industries.

After the GFC, the Fed also began buying mortgage-backed securities (MBS) – a practice that continues today. Gillman criticizes this as subsidizing the banking sector and artificially increasing the value of its assets. He even questions the legality of these actions.

To conclude, an efficient bank insurance system, such as the FDIC, is important for eliminating bank panics and contributing to a no-default equilibrium. However, because a portion of the banking sector (including investment banks) lies outside FDIC coverage, the insurance system is not fully effective, as evidenced during the GFC. Gillman believes all financial intermediaries should be included in the FDIC insurance system. He writes: “The policy of letting banks escape both the FDIC and the holding of reserves at the Fed during the deregulation of banking led to an extremely small quantity of reserves being held at the Fed when the bank panic hit in 2008” (p. 205).

In addition, Gillman states: “If the largest banks partially avoid the FDIC deposit insurance fees, get free taxpayer subsidies through interest on reserves, and can successfully lobby for rescue when things go wrong for their risky assets that are held in place of negatively yielding Treasury debt, then the Fed’s novel intertwining of money and banking policy is biased against the thousands of regular FDIC banks that play by the rules of an efficient bank insurance system” (pp. 174-175).

Phillips Curve

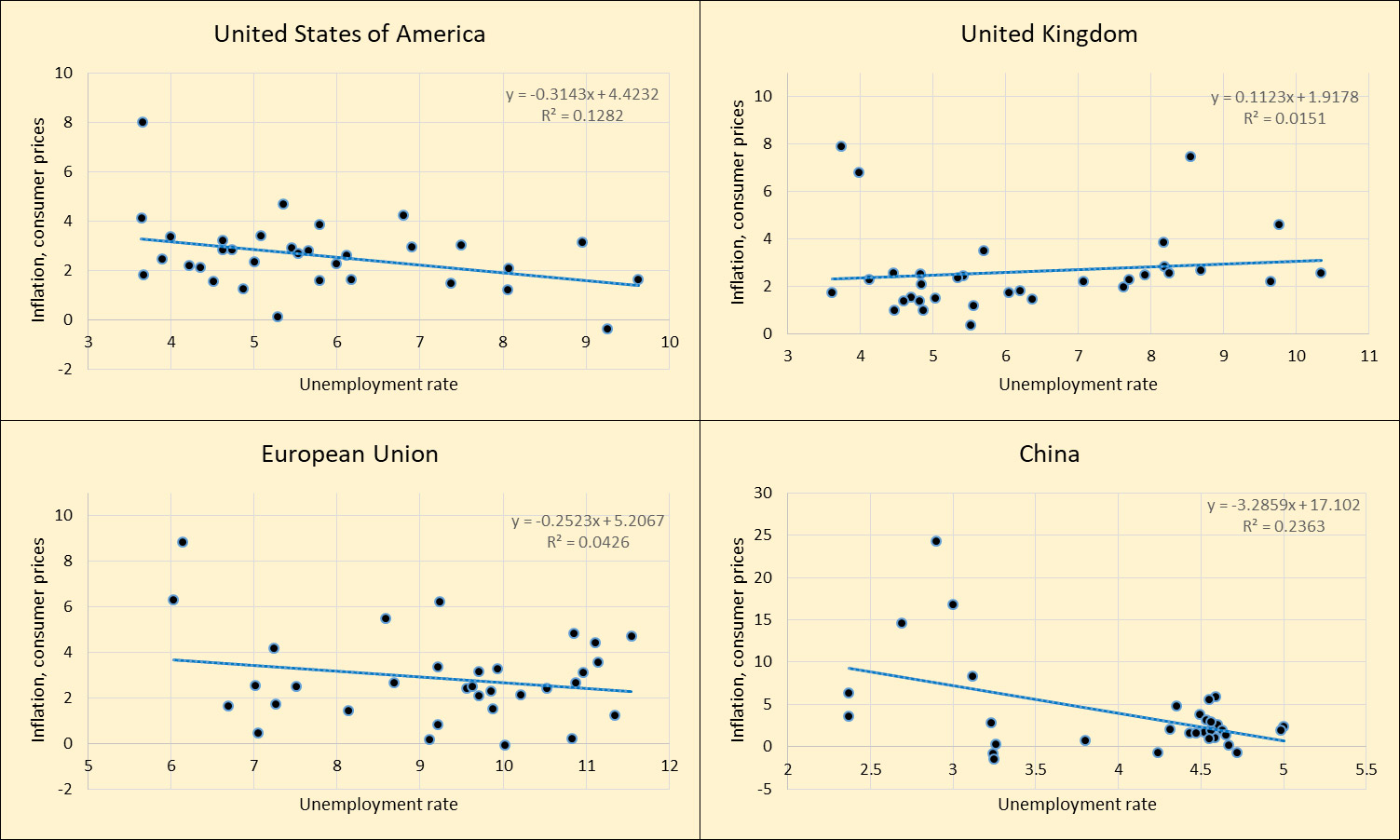

In his analysis of the UK and the USA, Gillman finds only a temporary—not permanent—inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment rates, observable in specific historical periods. Inspired by the assertion that there is no historically stable inflation-unemployment tradeoff, I collected consumer price index and unemployment rate data spanning 32 years (from 1991 to 2023) to construct Phillips curve models for the UK, USA, EU and China. As the below figure demonstrates, the Phillips curve appears predominantly flat across all four models, corroborating Gillman’s assertion that no permanent inverse relationship exists.

Static Phillips Curve models, 1991-2023

Source of data: World Development Indicators (2025)